Greenflation or Transformation? Unpacking Energy Prices in the Transition Era

As the world races to decarbonise, it is bumping up against a paradox: the green transition is material intensive. Solar panels, wind turbines, batteries and electric vehicles all require large quantities of copper, lithium, nickel, rare earths and other critical minerals. Demand for these inputs is surging as governments ramp up climate ambitions and firms invest in green technologies. At the same time, environmental contraints, tighter regulation and social opposition are making it harder and slower to develop new mines, expand extraction and build energy infrastructure. The result is upward pressure on prices for energy, metals and minerals, a phenomenon often dubbed "greenflation" 1, which threatnes to make the energy transition more costly, politically fragile and uneven across countries.

This is happening against a macroeconomic backdrop that is already fragile. Global growth has slowed from its post-pandemic rebound and is projected to remain below its historical average in the coming years (IMF, 2023). Inflation, while off its peak, is still elevated relative to pre-COVID norms, keeping real incomes under pressure and forcing central banks to maintain tigther financial conditions than in the 2010s (IMF, 2022, 2023). For highly indebted governments, with public debt rations close to or above 90% of GDP in many advanced economies, higher interest rates make servicing debt more expensive and leave less fiscal space to cushion energy shocks or subsidise green investment (OECD, 2024a). In this environment, sustained greenflation could aggravate stagflation risks, weigh on investment and fuel social pushback against climate policy.

This blog post explores how rising climate policy ambition interacts with commodity markets to generate volatility in energy and raw material prices, and how those dynamics spill over into broader inflation pressures. It asks whether greenflation is a temporary growing pain or a more persistent feature of the transition, and what that means for policymakers, firms and households. With tools such as difference-in-differences (DiD), panel regressions and event studies, Stata allows researchers and analysts to quantify how specific policy shocks, for example, the introduction if carbon pricing, changes in fuel taxes or new green subsidy schemes, affect energy prices and inflation expectations, while controlling for global demand, monetary policy and other macroeconomic confounders. Timberlake Consultants training, techinical support and bespoke consultancy services help users design these models, clean and structure data from sources like the IMF, OECD and national statistics, and interpret the results in a policy-relevant way. With the right combination of software, data and expertise, we can begin to seperate hype from signal and assess whether the greenflation is an unavoidable cost of decarbonisation or a challenge that smarter policy design can meaningfully mitigate.

1 Greenflation: Higher prices resulting from the adaptation of production processes to a decarbonised economy. It also includes the effects of carbon tax and public investment policies.

The Different Shades of Greenflation

When we talk about "greenflation", we are really talking about several overlapping sources of price pressure that all stem, in different ways, from climate change and the transition to net zero. ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel usefully breaks these into three categories: climateflation, fossilflation and greenflation (Schnabel, 2022; Baudchon, 2023).

-

"Climateflation' refers to price increases driven by the physical effects of climate change itself. More frequent and severe floods, droughts, wildfires and heatwaves disrupt production, damage infrastructure and reduce agricultural yields. That pushes up the cost of food and other climate-sensitive goods and can also increase price volatility as harvests become less predictable. Recent spikes in grain and vegetable prices after droughts in Europe, Asia and North America are textbook examples of climateflation (Schnabel, 2022).

-

"Fossiliation" captures inflation that originates in fossil fuel markets. When oil and gas supply is constrained, because of geopolitical shocks such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine, underinvestment in upstream capacity, or tighter enviromental regulation, energy prices surge and ripple through electricity bills, transport costs and industrial input prices. Fossilation was a major driver of the inflation spike Europe experienced in 2021-2022, when wholesale gas prices skyrpcketed and filtered into headline CPI (Baudchon, 2023).

-

Finally, "greenflation" in the narrow sense arises from the policies and investments needed to decarbonise the economy. Carbon pricing, stricter environmental standards and large-scale public and private investment in low-carbon technologies all raise costs in the short run. Firms must replace existing capital, pay higher carbon taxes and compete for scarce "green" inputs such as copper, lithium or nickel, which pushes up prices for a wide range of goods and services. Over time, these measures can deliver productivity gains and more stable energy costs, but during the transition they can be a significant source of inflationary pressure (Baudchon, 2023; Schnabel, 2022).

Understanding these three "shades" of greenflation matters for policy. Climateflation calls for faster adaptation and resilience investment; fossilation highlights the risks of continued dependence on volatile fossil fuel markets; and greenflation forces policymakers to design transition paths that are credible, gradual and well-communicated so that short-term price pressures do not erode support for decarbonisation. One of the most important, and controversial, tools in this toolkit is the carbon tax, which sits right at the intersection of climate ambition and inflation dynamics.

Carbon Tax The Inflationary Effect

As more countries commit to decarbonsing their economies, a recurring fear is that climate policy itself will become a new source of inflation. In 2021, Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, warned that the fight against climate change could fuel a sustained rise in prices. Central banks have taken note too: in its 2021 strategy review, the European Central Bank (ECB) explicitly highlighted climate risk, and Isabel Schnabel has argued that "greenflation", inflationary pressure arrising from climate policies, may need to be factored into monetary policy desicions (ECB, 2021; Schnabel, 2022).

At first glance, carbon taxes look similar to classic energy price shocks. A long literature shows that sharp increases in oil prices tend to be both contractionary and inflationary (Kilian, 2008; Hamilton, 2009), even if their macroeconomic. impact appears more muted today thanks to stronger monetary policy credibility and more flexbile labour markets (Blanchard et al, 2013). But equating carbon taxes with oil shocks is misleading for at least three reasons.

First, the magnitudes are very different. Typical carbon tax increases are small compared with the dramatic swings seen in global oil and gas markets. Second, energy price shocks are usually sudden and unanticpated (Konradt et al, 2023), while most carbon taxes are announced well in advance with clear schedules for future increases. This gives firms and households time to adjust technologies and behaviour. Andersson (2019), for example, finds that the carbon-tax elasticity of gasoline demand in Sweden is roughly three times larger than the standard price elasticity, suggesting that people respond differently when higher prices are clearly linked to policy and expected to persist.

Third, the design of climate policy matters enormously. Many carbon taxes are explicitly revenue-neutral: governments recycle the proceeds by cutting other taxes, rebating households, or funding green investment. In those cases, the average tax burden on firms and households need not rise, even if relative prices change. And because carbon taxes are implemented at the national level rather than through a coordinated global policy, their direct effects are largely confined to the domestic economy, unlike a global oil shock, which hits everyone at once.

Recent empirical evidence reinforces this more nuanced view. Konradt et al. (2023), using data for European countries and Canada, find that carbon taxes have not significantly increased inflation; in most specifications, the dynamic effects are statistically indistinguishable from zero. Any impact appears concentrated in headline inflation via higher energy prices, with little evidence of spillovers to core inflation. In other words, carbon taxes seem to reallocate relative prices, making carbon-intensive energy more expensive, rather than unleashing a broad-based, persistent surge in the overall price level.

Front-Loading the Inflationary Shock: Green Capex and Fossilflation

One reason the transition can feel inflationary in the short run is that it turns the traditional cost structure of the energy system upside down. Fossil-fuel power is typically low-capex, high-opex: once a plant is built, the bulk of the expense is the ongoing purchase of coal, oil or gas. Most renewable technologies are the opposite - high-capex, low-opex. You pay a lot up front for turbines, solar panels and grid upgrades, but once those assets are in place, electricity can be produced at very low marginal cost.

During the transition, we effectively run two systems at once. Governments and firms are still maintaining parts of the fossil-fuel infrastructure while simultaneously pouring record sums into new clean capacity.

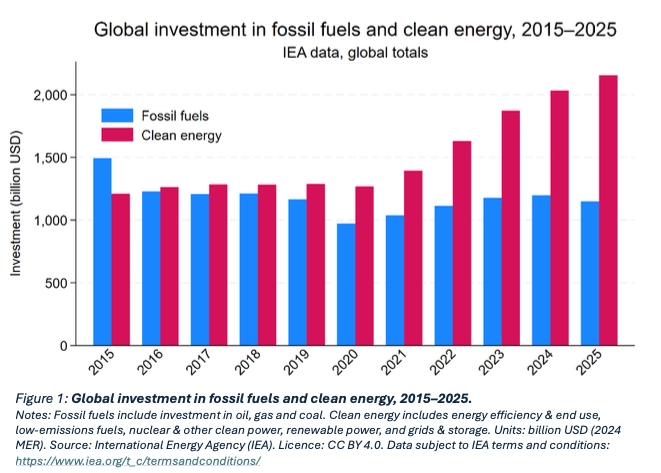

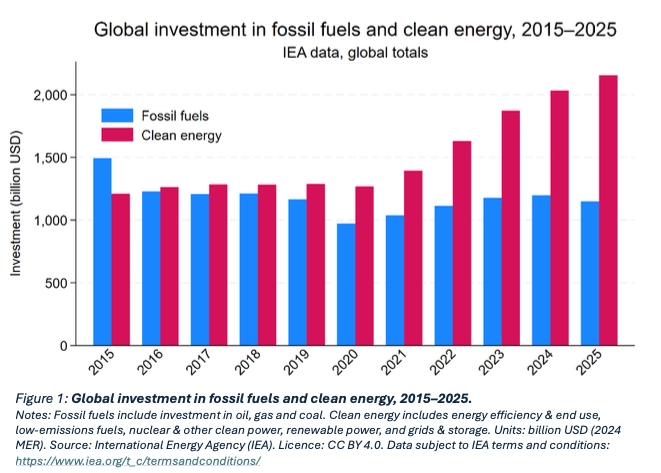

In Figure 1, the global investment data from the IEA make this shift very clear. Clean-energy spending rises steadily from 2015 onwards and, over time, overtakes and then decisively pulls away from investment in fossil fuels. Fossil-fuel spending is broadly flat to slightly declining, while clean-energy capex climbs year after year, especially after 2020 (IEA, 2023). The message is simple: the world is not yet spending dramatically less on fossil fuels, but it is spending far more on renewables, grids and storage, so total energy-system investment is higher than before.

This creates a period of “double capex”, in which societies effectively pay for two energy systems at once. That front-loaded investment hump can show up as cost-push pressure in headline inflation, a point emphasised in recent work by central banks and international organisations (Schnabel, 2022; IMF, 2022). The upside is that, once the build-out of renewables and networks is largely complete, the inflationary impulse should fade. With low operating costs and no fuel price volatility, a mature clean-energy system can deliver cheaper, more stable electricity over time. Because renewable resources are geographically more dispersed than oil and gas, countries that currently import large volumes of fossil fuels should also see their energy import bills, and their exposure to commodity-price shocks, decline in the long run (IEA, 2021).

The same transition dynamics, however, also set the stage for fossilflation. As demand for hydrocarbons peaks and the policy outlook becomes less favourable, producers have weaker incentives to maintain ageing fields or develop new ones. Given natural decline rates in existing deposits, even modest under-investment can translate into a noticeable drop in supply. With global oil demand expected to remain elevated for much of the 2020s in many baseline scenarios, this under-investment acts like a classic negative supply shock: fewer barrels chasing similar demand, and therefore higher prices (IEA, 2023; Schnabel, 2022).

Scenario exercises suggest that if upstream investment stays below what is needed to offset natural decline, oil prices may need to rise sharply just to keep markets balanced. Using standard demand elasticities, some studies estimate that this kind of fossilflation could add on the order of 0.8 percentage points per year to headline consumer price inflation over the next decade (Baudchon, 2023). Crucially, this does not represent a permanent shift in the trend of inflation, but a transitional surcharge, the price of moving from a fossil-fuel system that is cheap to build but expensive to run, to a low-carbon system that is costly to build but cheap to operate.

Recognising this front-loaded nature of the inflationary shock is vital for policy design. If governments and central banks treat every bout of green- or fossilflation as permanent, they risk over-tightening and choking off the very investment needed for the transition. If they ignore it entirely, they undermine inflation credibility. The challenge is to distinguish temporary, transition-related price pressures from persistent ones, and to manage this investment hump in a way that keeps both the energy transition and macroeconomic stability on track.

Conclusion: Greenflation as a Transitional Stress Test

Greenflation is often framed as proof that climate policy and price stability are incompatible. A closer look at the evidence suggests something more nuanced. In this blog, we look into three "shades" of climate-related inflation - climateflation, fossilflation and greenflation - reflect different mechanisms, and they call for different policy responses. Physical climate shocks demand faster adaptation and resilience investment; fossilation highlights the risks of relying on under-invested, geopolitcally exposed fossil fuel markets; and greenflation reminds us that the transition itself will temporarily raise some prices as we front-load capital spending on new, cleaner technologies.

The empirical literature on carbon taxes and inflation is particularly telling. Rather than behaving like sudden oil shocks, well-designed and pre-announced carbon taxes tend to shift relative prices without triggering broad, persistent increases in core inflation. Their impact depends heavily on policy design, tax rates, coverage, and how revenues are recycled back into the economy. Meanwhile, investment data from the IEA show a world running two energy systems in parallel: fossil fuel investment that is no longer rising, and clean energy investment that is accelerating. This "double capex" phase can add a temporary cost-push component to inflation, especially if fossil supply tightens too quickly, but it is best seen as a transitional surcharge on the path to a cheaper, more stable energy system.

For policymakers, investors and households, the key is to distinguish between temporary transition shocks and permanent shifts in inflation dynamics, and here central banks play a pivotal role. In an ideal world, there would be some degree of global monetary cooperation on transition-related shocks, with major central banks adopting a broadly consistent approach so that green- and fossilflation do not simply ricochet across borders via import prices, exchange rates and global interest rates. In practice, this is unlikely. The US Federal Reserve, as the pre-eminent global central bank, is likely to remain cautious about stepping too far into climate policy for fear of politicisation and threats to its independence, leaving most of the heavy lifting on climate to Congress and fiscal authorities. By contrast, the ECB and the Bank of England are more likely to pursue a cautious “do no harm” strategy at first, tilting collateral frameworks and, where relevant, private-asset purchase programmes towards greener assets, without formally changing their mandates. Over time, more ambitious options are conceivable, such as tolerating inflation modestly above target for a period, provided inflation expectations remain well anchored, in order to avoid over-tightening in response to temporary, transition-induced price spikes.

Robust empirical tools, such as difference-in-differences, panel models and event studies implemented in Stata, combined with the technical support and training offered by Timberlake Consultants, can help move this debate from anecdote to evidence. Ultimately, whether greenflation becomes a chronic drag or a manageable growing pain will depend less on physics and technology than on policy design and monetary strategy: how we price carbon, how we support vulnerable households, how central banks communicate and calibrate their responses, and how credibly we commit to a transition that is not only greener, but also economically and socially sustainable.

Francisca Carvalho, Lancaster University

Francisca is a third-year PhD student in Economics at Lancaster University. Her research focuses on climate risk factors and their impact on portfolio returns. She also teaches mathematics, econometrics, macroeconomics and microeconomics, to undergraduate and postgraduate students.

-

Andersson, J. J. (2019). Carbon taxes and CO₂ emissions: Sweden as a case study. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11(4), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20170144

-

Blanchard, O. J., & Riggi, M. (2013). Why are the 2000s so different from the 1970s? A structural interpretation of the changes in the macroeconomic effects of oil prices. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(5), 1032–1052.

-

Chung, C., & Kim, J. (2024). Greenflation, a myth or fact? Empirical evidence from 26 OECD countries. Energy Economics, 139, 107906.

-

European Central Bank. (2021, July 8). ECB’s Governing Council approves its new monetary policy strategy [Press release]. European Central Bank. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/search/review/html/index.en.html

-

Hamilton, J. D. (2009). Causes and consequences of the oil shock of 2007–08. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2009(1), 215–261.

-

International Institute for Sustainable Development. (2025, November 20). Five lessons from the IEA’s 2025 World Energy Outlook for the transition away from fossil fuels. IISD. https://www.iisd.org/articles/explainer/five-lessons-iea-2025-world-energy-outlook

-

Konradt, M., & Weder di Mauro, B. (2023). Carbon taxation and greenflation: Evidence from Europe and Canada. Journal of the European Economic Association, 21(6), 2518–2546.

-

Morison, R. (2021, June 18). The climate-change fight is adding to the global inflation scare. BNN Bloomberg.

-

O'Donnellan, R. (2021, December 13). Greenflation: Why the energy transition is sending commodity prices soaring. Intuition. https://www.intuition.com/greenflation-energy-transition-costs/

-

Olovsson, C., & Vestin, D. (2023). Greenflation? (Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series No. 420). Sveriges Riksbank. https://www.riksbank.se/globalassets/media/rapporter/working-papers/2023/no.-420-greenflation.pdf

-

Schnabel, I. (2022, January 8). Looking through higher energy prices? Monetary policy and the green transition [Speech]. American Finance Association 2022 Virtual Annual Meeting. European Central Bank.